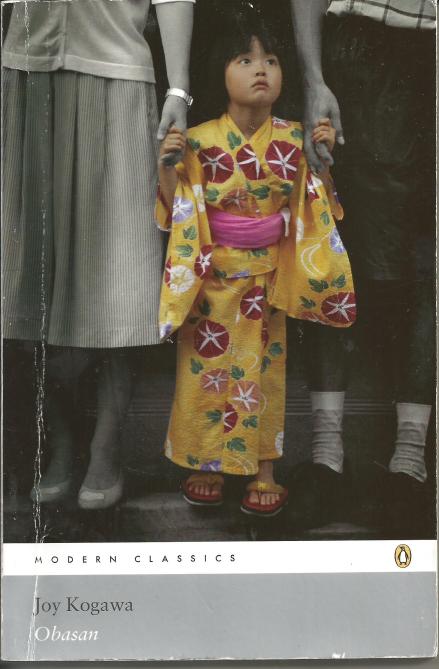

Sometimes we come to a book late. For me, Obasan, published in 1981, is one of those books. It is historically based fiction that reads like memoir – a hybrid, better than either genre. I’m reminded of a line from Yann Martel’s Beatrice and Virgil: “A work of art works because it is true, not because it is real.” Obasan is a work of art, a hard-as-stone story beautifully told.

Through Obasan, I travelled to another time, another culture, another horror of war and misguided political decisions. But Obasan is not a diatribe on political incorrectness; it is an intimate glimpse into people’s lives, love and loss, what was endured. In the end, insight and something that lurks between acceptance and forgiveness, a moving forward.

The narrator, Naomi Nakane, knows that “All our ordinary stories are changed in time, altered as much by the present as the present is shaped by the past.” She struggles to understand her childhood from her adult view and to grasp what it all means now. Her childhood was protected to a great degree, but Aunt Emily’s life was altered, split-away, and she knew the depth of loss and fought it with letters, but to no avail. When Naomi is grown, she receives a package from her aunt. “The fact is,” she thinks, jarred by Aunt Emily’s clippings and notes, “I never got used to it and I cannot, I cannot bear the memory. There are some nightmares from which there is no waking, only deeper and deeper sleep.” Perhaps it is easier to leave the blinders on and to not remember.

Despite the story’s dark theme, Joy Kogawa’s writing is sprinkled with light and lyrical passages. In one passage that particularly touched me, Naomi recalls a walk with her uncle: “The laughter in my arms is quiet as the moon, quiet as snow falling, quiet as the white light from the stars.”

Obasan is an important story: culturally, politically, and artistically. It is a beautifully told story that takes readers into the heart of experience. It neither shies away from, nor dwells upon, the hard historical reality that tore people’s lives apart. Canada’s story, without Obasan, would be incomplete. It is hard to face political wrongs, but they must be faced in order to be whole, complete – for all parties. As Yann Martel wrote in Beatrice and Virgil: “Stories – individual stories, family stories, national stories – are what stitch together the disparate elements of human existence into a coherent whole.”

Please read Obasan and think about the “silence that cannot speak.” Kerri Sakamoto, in the preface to my edition of the book, writes: “It was the authenticity of those words that so shocked me; the distillation of shame and muted fury….In the wake of the Pearl Harbor bombing, families – including my own – were taken from their homes, separated, and interned in camps simply because they looked like the enemy.” These words should haunt us all and make us think of their relevancy today as with others who come to make our country their own.

Available through your local bookstore or online: Obasan

Post script: for lovers of Japanese-themed stories

Two other “Japanese” books that have survived weeding from my crowded bookshelves that I recommend are Epitaph for a peach by David Mas Masumoto, an American-Japanese story (HarperSanFrancisco, 1995) and Snow by Maxence Fermine, translated by Chris Mulhern (Atria Books/Simon & Schuster, Inc, 1999).

Epitaph for a peach tells the story of an ending in California – the end of the peach farm – by a “third-generation Japanese American farmer [whose] lineage in agriculture dates back centuries. The Masumotos are from a solid peasant stock out of Kumamoto, Japan, rice farmers with not even a hint of samuri blood.” The U.S. experience of Japanese-Americans living on the west coast during WWII differed from the Canadian; there may have been hardship, but not the expulsion nor the confiscating of property.

Snow is a seeker’s story. It takes us on a lyrical search by Yuko through snow-covered mountains to find enlightenment…colour…and it is also an exquisitely told love story. If you like haiku, its simplicity and complexity, you will like Snow.

On my “to read” list: The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu. According to Martin Puchner (The Written Word), Murasaki’s “epic novel, The Tale of Genji, became a foundational text that influenced Japanese aesthetics for centuries to come.” Written about 1,000 years ago by an 11th century Japanese lady-in-waiting, The Tale of Genji is a story Puchner compares to the Iliad and The Epic of Gilgamesh. Puchner says, “Murasaki’s diary felt to me like a turning point in the history of literature—it sounds so recognizable, so intimate, so modern.”

“The fact that someone living in an extremely different time, halfway around the world, a thousand years ago, could whisper in my ear in that way—it’s magical. That experience is part of what draws me to world literature in general, a reminder of the power writing has to transport a voice across time and space.” (Quotes from a January 23, 2018 article by Joe Fassler, “The Technology Shift Behind the World’s First Novel, The Atlantic online.)