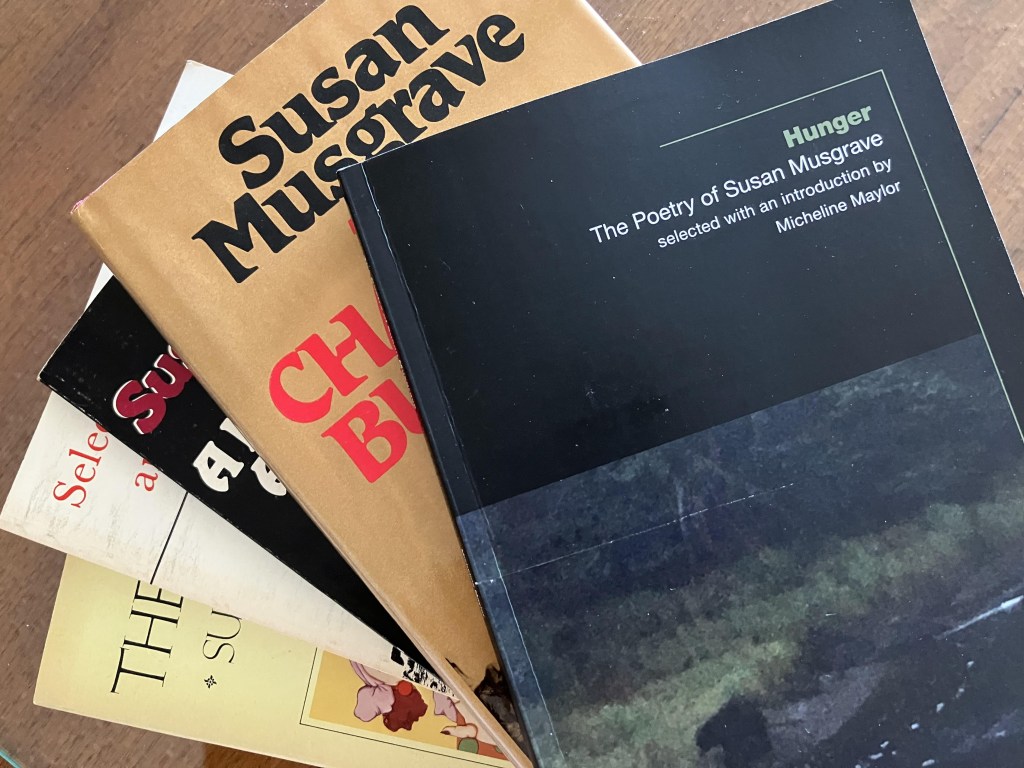

Back in the 1970s when I was at university, few female poets were invited for readings – poetry was a man’s game – and Susan Musgrave is the only woman that I recall reading at the university during that decade. I was hooked. During that time, I collected three poetry books and one novel, each autographed by Susan, along with a postcard note. (In another book, I found a slender feather used as a page marker.) To this small group of her early work, I’ve now added, Hunger: The Poetry of Susan Musgrave selected with an introduction by Micheline Maylor.

In the introduction, Micheline Maylor writes that Susan Musgrave’s “poetry is personal, intimate, confessional, esoteric, and infused with sadness…(xiii). Further along, Maylor writes: “Her impeccable use of grammar is that kind that causes poets a sort of aesthetic arrest. I could write an essay on the grammar in her poem ‘Tenderness’ from Exculpatory Lilies. The use of colons and question marks as midline-forced full stops gave me a new standard for structural parallelism and a kind of a craft that is a master class of internal enjambment and pacing at line level” (xx). ‘Tenderness’ is included in the collection as is an afterward by Susan Musgrave.

Each poem takes my breath away and I’m finding new favourite passages – “Lately I have come to believe / all that is of value is the currency / of the heart…” (“Origami Dove,” 27); “wild and alone is the way to live” (“Wild and Alone,” 47) in which she learns a life lesson from a mouse – besides the sadness, you will also find a little subtle humour (or so I’m reading it that way today). Like Musgrave’s Granny, brew a pot of strong tea and enjoy.

The Impstone by Susan Musgrave (McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1976)

Selected Strawberries and Other Poems by Susan Musgrave (Sono Nis Press, 1977)

A Man to Marry, A Man to Bury (McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1979)

The Charcoal Burners: a novel (McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1980)

Hunger: The Poetry of Susan Musgrave selected by Micheline Maylor (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2025)

Only five of the 35 books by Susan Musgrave. Wow!