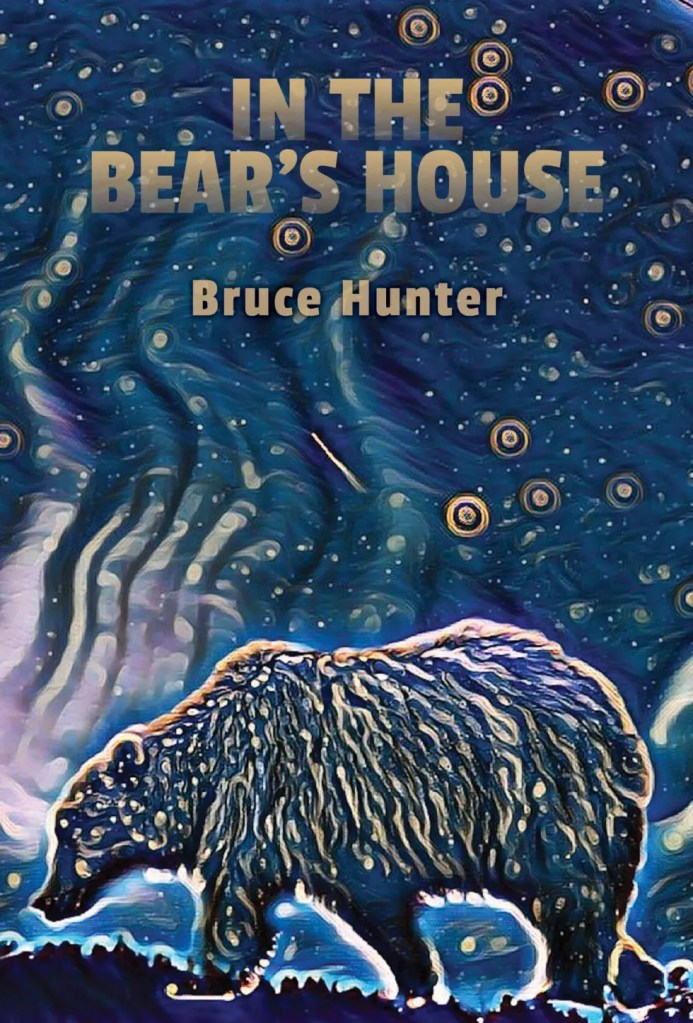

At first glance, In the Bear’s House by Bruce Hunter is a coming-of-age story, but it is more. In his twelfth book, award-winning Hunter weaves a complex braid of stories that sits comfortably beside W.O. Mitchell’s Who Has Seen the Wind and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, giving us the story not only of a boy who seeks the wisdom of an ‘outsider,’ but a story that captures a place and time that is now history but oh, so relevant. At the heart of In the Bear’s House is the fraught reality of a young deaf boy – Will/Trout – who is lost in his silent world and mostly misunderstood by schoolmates and elders. An angry boy, Trout acts out his frustration. This thread of the braid is told by an omnipotent narrator. The second narrator is Clare, Trout’s mother, who tells her story in alternating chapters. The third thread of the braid is ‘place and time’ which become a character. Hunter reveals Calgary on the edge of the oil boom as well as the Kootenay Plains at the time of the Bighorn Dam that flooded the territory of the Stoney Nakoda. Each of these threads could have become individual books, but Hunter skillfully weaves them into a heartbreaking story of our failure on all three fronts.

Seven of Hunter’s books have been poetry and this novel brims with poetic writing. One of the first tropes, which I noticed, is the conch shell, a shell that was carried to the prairies from Wickham, New Brunswick by Trout’s great-great auntie in 1882. She tells Trout, When I was a girl, we’d put it to our ears and hear the sea. I always thought it looked like an ear (30). Trout calls his early hearing aids contraptions; they, his auntie, and the conch are forever intertwined:

Through the crackle of his contraption, he listened, not to the sea, but to the river, the hiss of water, and once more, to his auntie’s stories (32).

The conch, a reminder of the gift of hearing and imagination. In the Bear’s House is grounded in 1960s Calgary and Kootenay plains, as W.O. Mitchell’s iconic novel, Who Has Seen the Wind, is grounded in the prairies. Hunter links the two protagonists, while also paying tribute to his mentor. He writes,

It was not the first book in which Trout recognized himself, but it was the first where he recognized the place in which he lived (59).

In the Bear’s House is more than an Albertan novel. You don’t need to be prairie- or foothills-born to find a piece of yourself in the story. . . .

To continue reading please go to Maple Tree Literary Supplement, click here.