I love a long poem and the collections that follow the narrative thread of a journey from page one to the end – whether it flows, as a novel, or whether it’s more of a sequence of shorter poems that unravel the story.

Ottawa poet Monty Reid says that “the sequence accommodates interruptions more readily, it stops and starts, tries to hold it together, begins again…. (interview by rob mclennan, above-ground press).

The books that I’ve selected to highlight today include both flowing book-length poems and sequence collections.

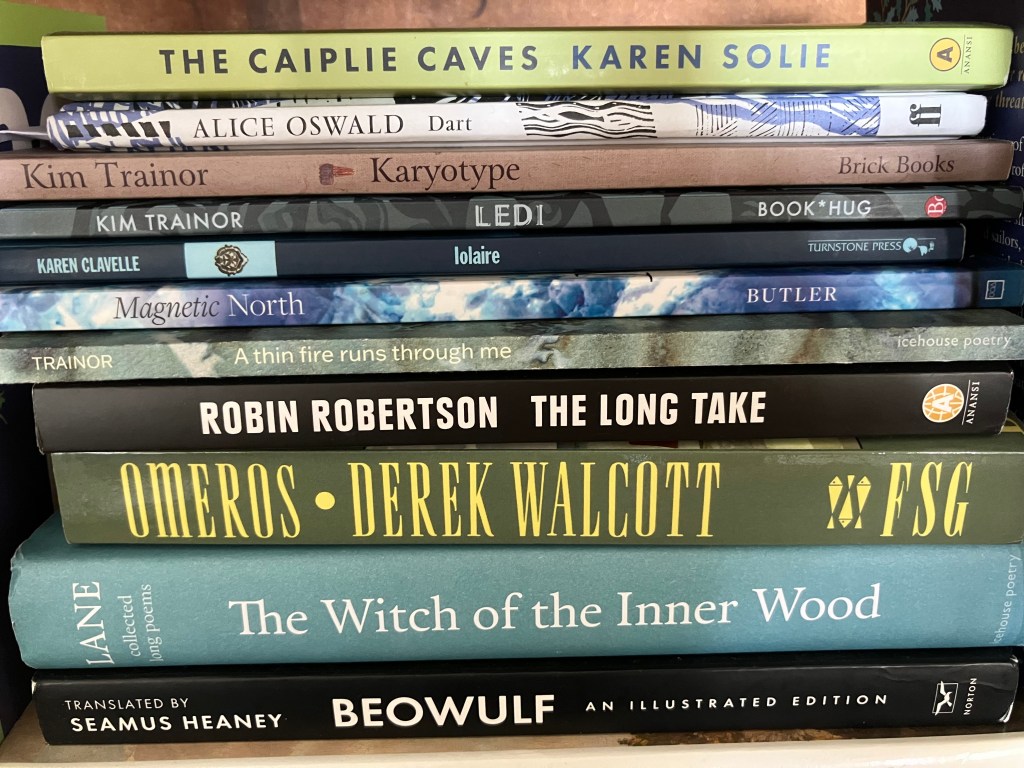

I’ve reviewed only two of the long-poem collections that have been sitting in my “to write about” stack. But it’s summer reading time, and I’m not going to get the job done. So here is a reading list to take you through August and beyond.

Two that I’ve reviewed:

- Beowulf translated by Seamus Heaney: an illustrated edition “is beautiful to read, vivid, alive,” to quote from my review (W.W. Norton, 2008). Click here.

- Iolaire by Karen Clavelle “is a hybrid telling of one of Scotland’s worse maritime disasters, a story of an island’s grief, a woman’s loss, and by the end, a new (though haunted) beginning” (Turnstone Press, 2017). Click here.

Others of the book-length form that I recommend as good summer reading include:

- Magnetic North: Sea Voyage to Svalbard by Jenna Butler (University of Alberta Press, 2018)

- Dart by Alice Oswald (Faber and Faber, 2002)

- The Long Take by Robin Robertson (Anansi, 2018)

- The Caiplie Caves by Karen Solie (Anansi, 2019)

- Three books by Kim Trainor: Karyotype (Brick Books, 2015), Ledi (Book*Hug, 2018), and a fragmented narrative, A thin fire runs through me (icehouse poetry, 2023)

- Omeros by Derek Walcott (Farrar, Straus, and Geroux, 1990)

And finally, a collection by M. Travis Lane titled The Witch of the Inner Wood. Like novellas, these poems celebrate the long poem format. Lane’s book marks the consistent achievement of one of Canada’s leading poets (icehouse poetry, 2016).