In this life, we are visitors no matter where we go / on this earth, the headstones remind us.

— “The Rooks in the Sycamores at the Tomb at Dunn” (98-107)

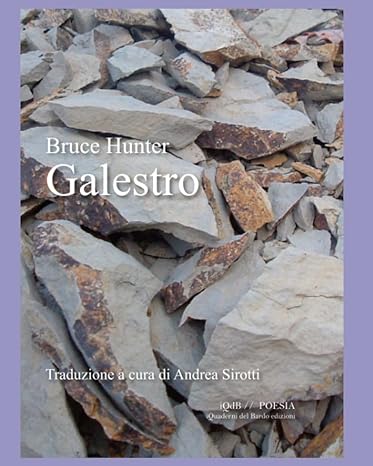

Galestro, of the book’s title, is the name of the mineral-rich and stony soil of Tuscany. It’s the hard till that nurtures the Sangiovese vines and the Chianti that flows through poems like love. Smooth-flowing Chianti and stony hard till are wonderful metaphors that thread throughout the collection. Perhaps it is for this “flow” that Bruce Hunter has arranged the poems without distinct sections. However, the poems have been carefully organized. In the initial poems, Hunter reflects on his youth and working years; the middle section celebrates Tuscany and love; and the last poem circles back, exploring a theme introduced early on. Individual poems are constructed on a framework of details, which of course creates the pull of authenticity, but we also find allusion, together engaging both our love of facts and our love of fancy.

One poem that reflects on Hunter’s young years in and around Calgary surprised me with the flavour of a Patrick Lane poem. In no way does the poem mimic Lane, which makes it hard to put my finger on what exactly made me sit up in my chair when I read “Skyhooks” (30-33). In the poem, Hunter begins by describing kites:

Each of them angling for light,

strung between existence and dream

trolling for skyfish or errant angels

lost in the lure of clouds.

But then he quickly moves to a tough work scene, the stuff of early Lane (and of Tom Wayman, too), before he brings humour into the poem. A complex juggle of tone, beauty, and grit.

The primary subject of the first sixty-five pages is the geography and people of Hunter’s childhood in Calgary and his adult life in Toronto, although there’s a wide range of themes and metaphors layering the poetry. Then, to celebrate his actual retirement, Hunter travels with his wife to Italy. It is here we gain the benefit of Hunter’s apprenticeship as a gardener and arborist (as he tells us in “Lost and Found in Cortona,” p 90-93). This deep knowledge creates the details that make the Italian poems so fascinating. It is also here, in these Tuscany poems that we see Lisa as lover-muse. For example, in the title poem “Galestro” (p 76-83):

I learned to read soil in my apprenticeship,

and sky and wind, on the highest point of land,

where rain is made, and wine,

somewhere between alchemy and prayer,

reverence and ritual….

Hunter is sensitivo in his knowledge of gardening, but there’s been a subtle switch and suddenly Lisa, his wife, is sensitiva:

…the woman who teaches the heart,

who reads my eyes, who calms the animals, heals the beloved.

This is Bruce Hunter’s tenth book. His writing apprenticeship has led to multi-layered poems that offer at once a clear, straightforward read and, if you sit with them, a complex understanding of life, love, and endings. Much of my recent reading has included single-theme collections and book-length poems. Reading Galestro has forced a re-think. Hunter’s voice, as you can see, is wide-ranging. I’m breaking free of my mold.

For another example of Hunter’s versatility, “Ligurian Poppies” introduces the poet as witness:

Bomb cracks in the University of Bologna.

The missing towers of the Castello.

Neptune can hold back the sea

but not the vile will of hard men.

The collection is all metaphor.

In “The Rooks in the Sycamores at the Tomb at Dunn” (98-107), the final poem in the collection, Hunter reflects on a visit to the far northeastern edge of Scotland, Caithness, the Tomb of Dunn and of Hunter’s forebearers:

The tomb’s open now, pillaged.

The plank lid torn off and left where it landed.

Vines cover the chapel’s window-less walls.

The roof long ago gone….

//

And there’s an alder sapling between their graves.

Seeds from the ancient forest brought up by gravediggers.

One day the alder will crack the stone.

Trees stronger than stone in their kinetic lift.

When we search for the ancestors, for what are we searching? Hunter takes us on a journey through language and naming, through mythic and physical places, concluding the poem and collection with: and if I had one wish: / I be that tree, / stronger than stone in its lift. / And that my friends, is the gist.

What is there to say after that?

Galestro is a big book (8 x 10 inches, 122 pages) of poetry by Bruce Hunter, translated from English (on the left page) into Italian by Andrea Sirotti (on the right). It is a pleasure for word-lovers to see how the words fall and follow, a treat to compare and imagine how they sound and what they evoke in the second language.

Galestro, Quaderni del Bardo (2023) by Bruce Hunter

Available through your local bookstore or online: ISBN 9798376256602