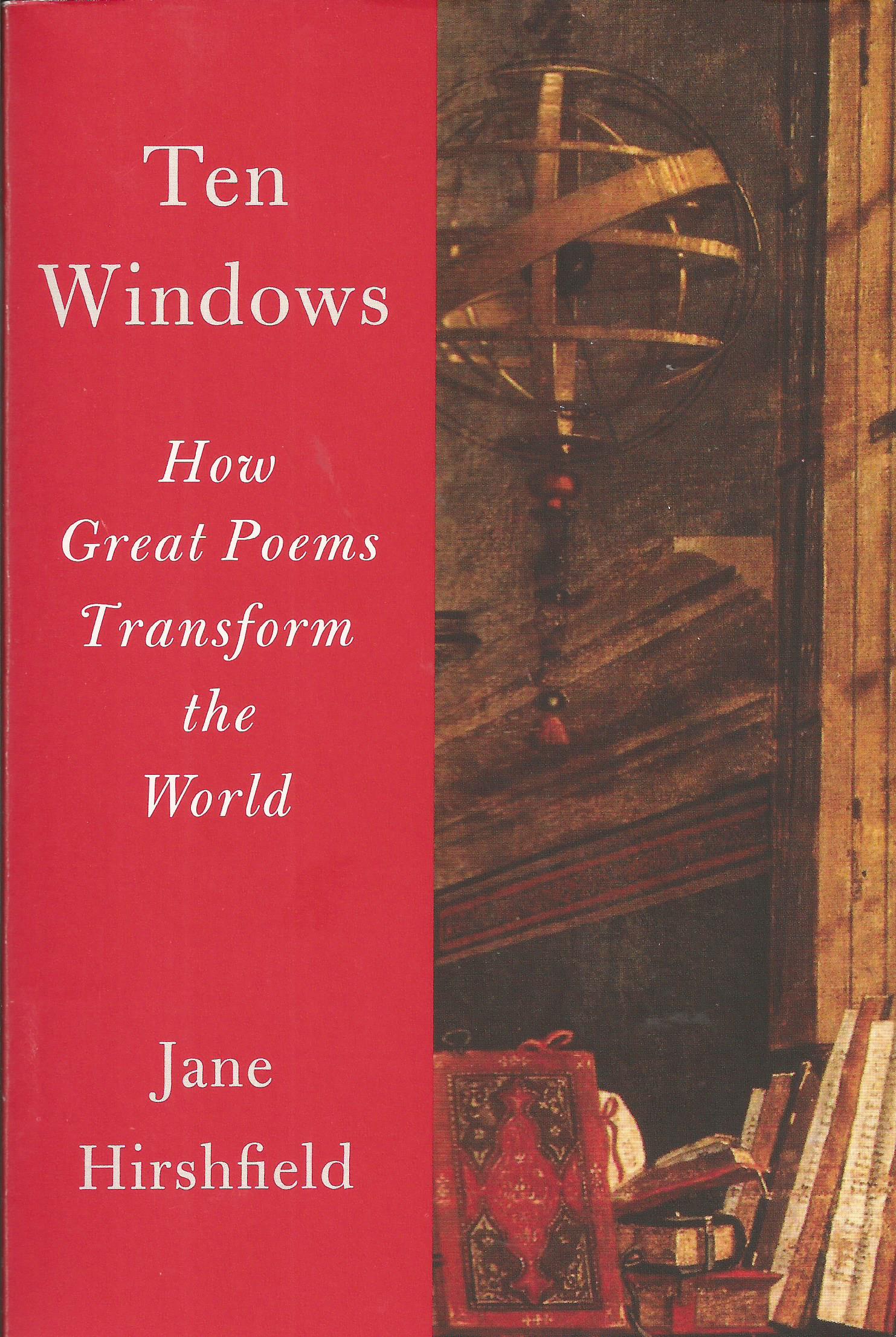

Jane Hirshfield’s words perceptively reveal the seduction of poetry, of art. They open windows of clarity while simultaneously celebrating ambivalence and paradox. Ten Windows provides both a brilliant journey and practical guidance through the world of poetry for both readers and writers.

Poetry’s addition to our lives takes place in the border realm where inner and outer actual and possible, experienced and imaginable, heard and silent, meet…In a poem, everything travels inward and outward.

The essays in Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World lead us from what is inherent in poetry (and the other arts) through metaphorical windows of language, image, sound/music, hidden/unsaid, ambiguity, surprise, transformation, and more. Throughout, Jane Hirshfield reminds us of the importance of poetry in our lives, how it reflects culture, and how it can even change cultural borders.

In “Seeing Through Words: An Introduction to Bashō, Haiku, and the Suppleness of Image” (Chapter Three), Hirshfield writes, “…if you see for yourself, hear for yourself, and enter deeply enough this seeing and hearing, all things will speak with and through you.” Haiku was not new when Bashō came around in the 17th century, but he changed it and influenced writing since. Bashō sought more from the form than did his predecessors. He sought

…to make of this brief, buoyant verse form a tool for emotional, psychological and spiritual discovery, for crafting new experience as moving, expansive, and complex ground as he felt existed in the work of earlier poets. He wanted to renovate human vision by putting what he saw into a bare handful of mostly ordinary words, and he wanted to renovate language by what he asked it to see.

Even for poets who veer from the Haiku form, this goal is an ambitious one. In this small poem of image and sound, Bashō excels in meeting the challenge:

seas darkening

the wild duck’s calls

grow faintly white

In Ten Windows, Hirshfield reminds writers and readers to see what isn’t said, to read between the lines. To me, this poem speaks volumes beyond what Bashō saw; it stirs emotions of darkness, of the fleetingness of experience, and of things disappearing/lost. Hirshfield notes:

“The reader who enters Bashō’s perceptions fully can’t help but find in them a kind of liberation. They unfasten the mind from any single or absolute story, unshackle us from the clumsy dividing of world into subjective and objective, self and other….

In a chapter about uncertainty, Hirshfield reminds us:

Poetry often enacts the recovering of emotional and metaphysical balance, whether in an individual (primarily the lyric poem’s task) or in a culture (the task of the epic). Yet to do that work, a poem needs to retain within its words some of the disequilibrium that called it forth, and to include when it is finished some sense also of uncomfortable remainder, the undissolvable residue carried over—disorder and brokenness are necessarily part of human wholeness.

A couple of paragraphs on, she continues developing her idea: “The most serene works on the bookshelf are…in the lineage of Scheherazade’s stories—art holding incoherence and death at bay by invention of beauty, detour, and suspense.” In the colloquial, we say show, don’t tell; leave something to the reader’s imagination; tie up loose ends, but leave the door open.

A work of art is not color knifed or brushed onto a canvas, not shaped rock or fired clay, a vibrating cello string, black ink on a page—it is our participatory, agile, and responsive collaboration with those forms, colors, symbols, and sounds.

Later, in the transformation chapter, Hirshfield writes:

The experience of art takes place within and under the skin. When we read the word “orange,” neuroscientists have found, our taste buds grow larger, more so if we are hungry. A mountain in a poem is known by what has been motionless and stony in us, and by what we have internalized of rock and steepness through legs and eyes. The characters of a story or play are lent our lives’ accumulated comprehensions and history, in order to make theirs our own.

Writing and reading is collaborative. “Poems are made of words that act beyond words’ own perimeter because what is infinite in them is not in the poem, but in what it unlocks in us.” This can be said of all art forms. Jane Hirshfield’s words perceptively reveal the seduction of poetry, of art. They open windows of clarity while simultaneously celebrating ambivalence and paradox. Ten Windows provides both a brilliant journey and practical guidance through the world of poetry for both readers and writers.

Available through your local bookstore or online: Ten Windows